John Hopkins to Study Impact of Service Dogs on Veterans with PTSD

What makes this study different from other studies?

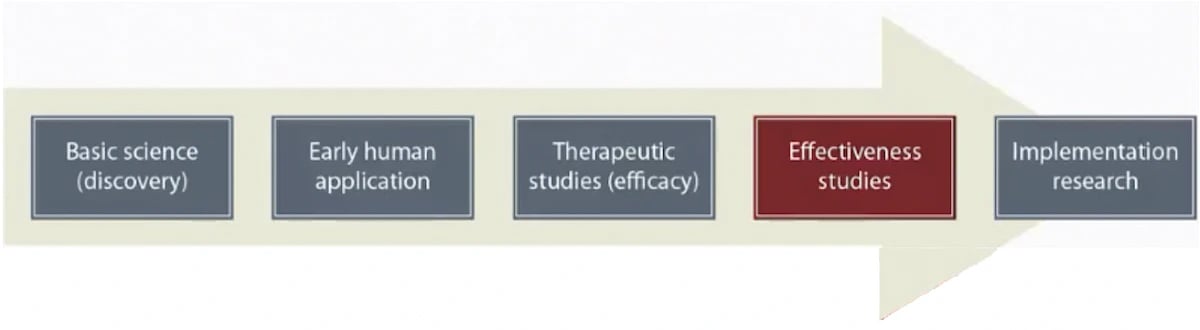

Although PTSD has been widely researched among the veteran population, little is known about the potential therapeutic benefits service dog assistance could offer this population. Fortunately, there has been a recent growth in interest, including two major research projects conducting empirical study of service dogs and their support of disabled veterans. First, in 2018, Purdue University conducted a proof-of-concept study examining the efficacy of service dog support among veterans clinically diagnosed with PTSD.1 This study produced several promising findings associated with the use of service dogs, however, the study sample was limited to recruitment from only one service dog provider organization, which served veterans from the post 9/11 Iraq and Afghanistan wars only. Our study differs by transitioning from efficacy in a proof-of-concept study (can it work under optimal circumstances?) to more pragmatic effectiveness (does it work under more common circumstances?) (Figure 1).

Our current study samples veterans recruited from nine service dog provider organizations, selected for their variation in size and geographic location. These organizations provide service dogs for veterans from any military service period, and not only the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. This is an important distinction since the majority of veterans cared for by the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) generally remain veterans from previous war eras, i.e., the Gulf War and Vietnam, and the most recent national veteran suicide prevention annual report found veterans ages 55 to 74 had the highest incidence of suicide.2 Moreover, in 2018, the average age of an Iraq or Afghanistan war veteran was approximately 33 years and this service cohort is largely not expected to enter the VA Health Care System until the year 2035, when they will reach middle-age.3 Thus, the impact of service dog assistance remains unknown among large veteran cohorts who already receive care from the VA Health Care System. Furthermore, no previous study has included qualitative interviews from the veteran participants, which is an important part of our study – to interview veterans receiving service dog assistance as well as interview organizational leadership.

It is not only important to translate evidence-based interventions into practice, it is also critical to consider many contextual factors, including organizational culture and practice,4,5 and the characteristics of providers,6,7 that impact intervention adoption. Therefore, in addition to examining whether service dog assistance successfully addresses trauma recovery in this population, our study evaluates the context in which the intervention is delivered. This study will apply translational science research and mixed-methods to evaluate the following aims across our several service dog providers:

(1) to describe the change in behavioral health outcomes (i.e., PTSD, anxiety, depression, resilience, social functioning, companionship, psychological well-being, work productivity, and general health status) among veterans working with a service dog, compared to veterans seeking service dog assistance;

(2) to understand from the veterans perspective, the role the service dog plays in daily life tasks, and the barriers and facilitators of a good working relationship with the service dog; and,

(3) to explore the perspectives from service dog providers about experiences of veterans, predicting success, barriers and facilitators.

What impact could the findings of this study result in?

Our study addresses several critical gaps in the related field of research. First, the field lacks rigorous data on the effectiveness of service dog assistance for veterans who are diagnosed with PTSD. Second, no formal qualitative evaluation of the veteran service dog experience or organizational leadership as key stakeholders have yet been reported. Third, building an evidence base can serve as a viable model for other similarly trauma-affected populations, including the first-responder community. We are using mixed-methods, i.e., survey research and interviews, to address these specific aims to provide a more complete evaluation of service dog programs, than would be in one approach. Linking complementary methods provides a more complete understanding of processes and barriers to effectiveness of program goals from the view of veteran service dog handlers and program provider leadership. Furthermore, this study will help inform policy-makers on the health benefits of service dogs. Thus, the potential benefit of this study is the opportunity for greater knowledge to be gained on the understanding of a vulnerable population affected by trauma, as well as how the use of service dogs can better address and promote mental health recovery among this population and other closely related trauma populations, i.e., first responders. The value of knowledge gained from this study will benefit service dog provider organizations located across the US, which can guide improvements to implementation for more than two-million veterans that could benefit from service dog assistance as a form of treatment for PTSD.8

References

- O’Haire, M. E., & Rodriguez, K. E. (2018). Preliminary efficacy of service dogs as a complementary treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder in military members and veterans. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 86(2), 179.

- Lutwak, N., & Dill, C. (2013). Military sexual trauma increases risk of post-traumatic stress disorder and depression thereby amplifying the possibility of suicidal ideation and cardiovascular disease.

- Geiling, J., Rosen, J. M., & Edwards, R. D. (2012). Medical costs of war in 2035: long-term care challenges for veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan. Military medicine, 177(11), 1235-1244.

- Glisson, C., & James, L. R. (2002). The cross‐level effects of culture and climate in human service teams. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 23(6), 767-794.

- Schein, E. H. (2004). Organizational culture and leadership Third edition.

- Ottoson, J. M., & Hawe, P. (2010). Knowledge Utilization, Diffusion, Implementation, Transfer, and Translation: Implications for Evaluation New Directions for Evaluation. Vol. 124. Hoboken.

- Feldstein, A. C., & Glasgow, R. E. (2008). A practical, robust implementation and sustainability model (PRISM) for integrating research findings into practice. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 34(4), 228-243.

US Department of Veterans Affairs. (2018). How common is PTSD in veterans? [Website]. Retrieved on January 28, 2021, from https://www.ptsd.va.gov/understand/common/common_veterans.asp.